After a geography degree with some development economics thrown in, I flew to Zimbabwe and lived for two years working in a remote school on the border of Mozambique up in the Eastern Highlands. It helped me to grow up, find something that I believed in and that I thought I could eventually be good at. Since then I’ve taught all over the UK but nothing will replace those first steps in the classroom in blazing temperatures and classes of 52. Recent UK government ideas to expand grammar schools has made me reflect on the inequalities in the two-tier education system during my time In Zimbabwe, and what has happened since.

1988 – To arrive in Africa! A 12-hour flight to Harare the capital, then a 6-hour long slog-drive, and a further 35 k’s down a tortuous mountainous dirt road, to the achingly beautiful but remote and dusty corner of the country on the border of Mozambique. The amazing welcome, the wildness of the ‘bush’, the huts and kraals. The mind-boggling maze of dust paths. To be slowly Incorporated into that different, young and vital culture. At a key point in a nation’s history – a ‘revolutionary’ history in the making. The initial laughter of cultural faux pas. Me striving to overcome our in-built English offhand, distant manner. The filling up of long, lonely, dark evenings with books, marking, reading. Falling asleep to electric cicadas and crickets, droning mosquitoes. The reality of actually being here!

I learnt how to teach in Nyanga High School, in the Eastern Highlands, a mission school run by the Canadian catholic Marist Brothers and led by the brilliant Zimbabwean Headteacher, Peter Muzawazi. Back then Mozambique was in a civil war and Renamo guerillas would sometimes make incursions across the mountains into Zimbabwe, which was slightly unnerving, but mostly it was perfectly safe, and a fantastic place to live for 2 years. And what’s not to like about wearing shorts all day?

The 450 boys at our school, whose parents were usually subsistence maize farmers, took an entrance exam at the end of primary to get into the mission school, so it was effectively a grammar school for black Zimbabwean children. Most white Zimbabwean children in the east, whose parents were mostly coffee farmers, were sent to private schools in the capital Harare. Our boys boarded at the school paying a nominal fee (subsidised from Canada) to pay for very simple food (mealie meal, vegetables and sometimes meat), and basic beds and toilets. We had the priceless benefit of electricity for at least 4 hours a day.

“At the end of an exhausting court case in Johannesberg I drove an old ANC leader to his house in Alexandria one night. On the way I propounded to him that well-worn theory that if you separate races you diminish the points at which friction between them may occur and hence you ensure good relations. His answer was the essence of simplicity. If you place the races in one country in two camps, he said, and cut off contact between them, those in each camp begin to forget that those in the other are ordinary human beings, that each lives and laughs in the same way, thT each experiences joy and sorrow, pride or humiliation. Thereby each become suspicious of the other and each eventually fears the other, which is the basis of all racism” Andre Brink

Most of the mission schools like ours were built before independence by enlightened Catholic and Anglican organisations who were also sponsoring the anti-apartheid effort south of the border, to make education possible for black students outside the cities. The mission schools struggled through the civil war. Many, like ours, were closed down because of the danger to children and teachers. The atrocities committed and the fear those atrocities instilled in the people were not all one-sided. The oldest man working on our mission, a cook, Sekuru Mambira was tortured first by the white Rhodesian security forces for not giving information concerning rebel movements, and then by the rebel guerillas because they believed he had talked to the Rhodesians. He was the gentlest man I met in my two years there, and remains one of my great role models.

The journey from the capital to the school was a kaleidoscope of colour. The hazy golden highveld: sunbaked plains shimmering with tobacco, coffee or maize gave way to the mountains and rocky inselbergs of the East. Going by local bus took twice as long as a car but it was so worth it to see real life. If you could get on a bus you were lucky. You’d cling on, hoping a seat would appear at some stage. Bank managers on the way home from the capital rubbed noses with peasant farmers who had been selling tomatoes in the next market. Chickens squawked about the bus until they were scooped up by women in fantastically coloured ‘zambia’ wraps. Dinner beckoned.

Education was effectively tiered: a tiny number of white ‘private’ schools, a very small number of well-established black ‘mission’ schools and thousands of brand new black ‘rural district council’ schools. What was amazing was the feeling of positive energy and political clout of the schools, in a country with 50% of the population is under the age of 15. Independence triggered a massive school building programme and recruitment of teachers to educate the children of parents who had never had this chance. I was recruited along with many teachers from Canada, Spain, Belgium, Ireland as part of that demand. Mission schools were pre-civil war so it was the new District Council schools that were the revolutionary flagship. School attendance for Zimbabwean primary children reached 95% in 1990, and literacy 91%, the joint highest in Africa at that time (it has never since reached that figure). Education embued the country with tangible excitement in the future. Children were desperate to escape the hot, dusty, drudgery of their parents’ and grandparents’ lives growing maize and vegetables. Education would be the silver bullet to help them do just that. It was a brilliant place to be a teacher. In the eyes of the local people, teachers were up there with the Gods. Even on a par with national football players!

While the living conditions of the children in mission schools cannot be compared with the traditional ‘white’ schools, the academic results were far better. Children sat Cambridge international exams, and performed well. All of the government leaders at the time including Mugabe were educated at mission schools. Nyanga High was a school that parents wanted to get their children into. Mostly the quality of teaching was good in comparison with the rest of the schools locally, and the government actually physically relocated teachers to schools across the country. Although this policy was brutally disliked by teachers (imagine a teacher in Newcastle told they had to up sticks with their family and go and teach in Ramsgate), this meant that in principle the best qualified teachers and heads were well spread across the country, serving rural areas as well as cities. This redistribution of skills into the hard to reach corners of the country sounds enlightened to us today in some UK schools where it may be hard to recruit because of our school’s geography, and followed the fashionable grassroots approach to development & the communist philosophy popular in Mugabe’s 1990s government. In reality however there was still a steady and insidious drift of teachers towards the capital Harare. The same ‘bright lights’ drift, which drains every rural area of its brightest talent in every developing country in the world, was steadily killing Zimbabwe’s backwaters too. Because of this dissatisfaction, and despite the school’s strong reputation, often teachers didn’t want to be there, so didn’t turn up for class, or would disappear and take the trip to the beer hall 6 miles walk away, leaving young people alone in their classrooms or on the football field.

“The rains were so late that year. But throughout that hot, dry summer those black storm clouds clung in thick folds of brooding the darkness along the low horizon. There seems to be a secret in their activity, because each evening they broke the long sullen silence of the day, and sent soft rumbles of thunder and flickering slicks of lightning across the sky. They were not promising rain, they were prisoners pushed back in trapped coils of boiling cloud” Bessie Head

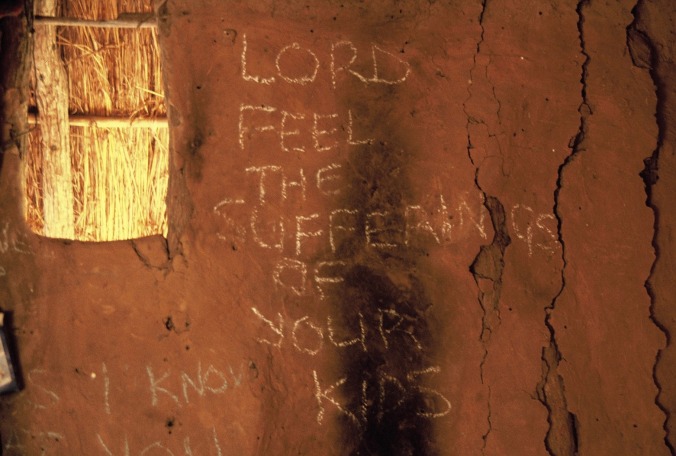

Living with me also based on a mission station were other volunteer teachers who taught in the flagship new Rural District Council schools. These were the vast majority of Zimbabwe’s schools, the poorest schools; think classic African open-roof classrooms, overarching purple jacaranda trees, hundreds of small children with smart, brightly-coloured maroon uniforms and you have it. Walls, if they had them, were clumsily built and experienced teachers & heads were a distant dream. Many classes were taught by students who had just matriculated from the oldest class in the school aged 15 or 16. There were no blackboards and textbooks were a luxury. I felt a certain guilt about teaching in a selective school, even though it was badly equipped and poor, when resources were so much worse in the rest of the local schools. I persuaded myself that my focus should be the kids in front of me and to make sure I taught as best I could, so that my students would get good grades and go on and reach the University of Zimbabwe, and perhaps so that some could even form the next government and bring about some sanity to the political situation. Most of us in the mission schools recognised that we needed to support colleagues in District Council schools, who had fewer resources and fewer qualified staff. Mostly I just loved the students in front of me who kept me on my toes intellectually and made me laugh, and made my job a true vocation. They made me fall in love with teaching, in a visceral way.

Africa should be a teacher’s paradise: Bright, inquisitive, resourceful children eager to learn and impeccably behaved. For the teacher of English there are classic African authors – Dambudzo Marechera, Doris Lessing, Chinua Achebe, Ben Okri. For the geography teacher a whole new wild, arid landscape opens itself to the eye. For the history teacher the intricacies of the disturbing colonial era and the ‘chimurenga’ struggle of the Civil War. The kingdoms of Chaka, Lobengula, Mzilikazi: Evocative names which spread great webs of power across the plains out towards the Kalahari. I taught with and learned from some cracking teachers: Peter Muzawazi was wise and fiercely competitive about his own school and children; Augustine Baudi was a deeply intellectual man-mountain who taught a firebrand of anti-colonialist history with brilliantly dark humour. Netsai Mugwindiri persuaded young minds to celebrate & hold onto their ‘Shona’ mother tongue and blend this with English lit. She taught local dialect and Chaucer, often in the same lesson!

In the afternoon the school grounds resounded with the screams and whistles of football matches, as we braved the heat and I played with the boys who zipped skillfully round me, always barefoot. Shoes were the most outward sign of wealth; football boots a fanciful dream. Sixth formers would carry their desks into the cool breeze and the shadows of the small mango orchard, beneath swaying eucalyptus trees blue against the backdrop of a smouldering Mt Muosi. They studied Keats, organic chemistry, or the evils of colonisation. They wanted to become lawyers, doctors, politicians, agitating reporters. They succeeded.

In November it was strange but somehow rather natural the way everyone seemed to be waiting, waiting for the rain. At midday the heat was oppressive and people stayed out of the sun. Old men sat in the shade and carefully studied the sky. Old women relaxed in the huts telling stories and shrieking at the best ones. Everything else is in the landscape itself seemed to wait, hovering in the heat. The mangy dogs would hardly stir except for the interruptions of the flies; dead carcasses with flicking years. The classrooms were cool places at this time, the children sat shirtless.

Looking back the tragedy was that children were being dangled expectations way beyond what the country would ever be able to deliver. There was just not the infrastructure for serious careers outside of farming, and although secondary industry grew through Chinese and British investment, there was no serious growth beyond this. In the best District Council schools there was an academic curriculum which also embraced agriculture, and I often saw specialist teachers who in the morning would teach Shakespeare’s Macbeth (within the vivid context of ancestral spirits and witchcraft) and in the afternoon discuss the merits of cash crops versus subsistence farming, or drip irrigation, or how to harness fish-farming to improve the family diet. But despite many inspiring headteachers fighting against the odds and delivering miracles on a daily basis, all too frequently schools closed because of embezzled school fees, or classrooms remained empty of teachers and full of children, hungry in every sense of the word. And of course there was no central leadership college or effective training program or to improve teacher quality, strengthen subject knowledge or the skillset of headteachers. And often teachers would not get paid at the month end. It is the ultimate irony that despite the failure of the education system, Mugabe ended up creating a young educated intellectual elite (including some I taught in Nyanga) who ended up at University of Zimbabwe demonstrating against his failed policies and violent means.

Winding down for the close of term. Exam season. Not a gentle smoothly programmed wind down but we are spluttering to a close with no direction rather like a car with engine trouble and no steering wheel, meandering its way to the bottom of the hill. Boys sit behind the desks twiddling their thumbs. Laughter trickles out of each classroom. Exam scripts lie idle and red ink-less in the staffroom. Headteacher nowhere to be seen. The hot day buzzes on, like the last.

And so a strange inequality grew across the whole country. Small numbers of well resourced, well staffed, and usually better led high-performing ‘mission’ or ‘grammar’ schools surrounded by swathes of District Council schools housing the majority of the population, with an inadequate buildings and untrained teachers. And where was the appetite for change to reform this desperately unfair system? Since the country’s decision-makers of course sent their children to Zimbabwean mission schools or to independent schools south of the border in South Africa, there was none. And so the gap between the relatively higher standards in mission schools, and the District Council schools grew. There was plenty of high-level talk of the grand plan for restructuring education and delivering ‘liberation’ to the children of the civil war heroes who had freed the country from colonialism. But not much evidence of results.

On the ground nothing changed for the poor and landless peasant farmers whose children attended the poorest schools. The same kinds of children went to the same kinds of the schools. Either from mission schools to university in Harare, or from District Schools straight back to the fields. Standards have not improved, and since the 1990s many schools have closed. The approach of Mugabe and Zanu PF has rightly received a lot of attention in the press in the last 20 years. However what has been almost unreported is the collapse of the education system beneath Mugabe’s failed economy, and the crushing disillusionment that children, parents and teachers in the system now feel. There was a moment when education could have transformed the country and the been a case study for the kind of ‘social mobility’ that we now talk of pupil premium funding being able to galvanise in Britain. That moment has gone. Many schools are now empty, many former teachers unemployed or gone. What began as an egalitarian dream has evaporated in the tropical sun.

“Those wonderful, terrible droughts have stripped the veld so that you could see the very bones of the Earth. Like a sheep’s skeleton. Until you arrived at a point beyond despair and cursing and fear, and in a stillness you’ve never known before. I remember that there was something so utterly clean and pure about the feeling. And only then, usually, the rains would come” Andre Brink

And finally the rains have come. Yesterday the rain and the hail came under the door blown by strong wind from the mountains and my exercise books on the floor were soaked. Some visitors from a faraway school were stranded on the dirt road and had to wait for the flash-flood rivers between them and us to die down. The snakes, long dormant, have begun to show their unwelcome faces once more. Brother Emmanuel, a sort of catholic Crocodile Dundee, has caught 2 bright green boomslangs and an Egyptian Cobra in the last two days. Still the wind thunders outside and we are treated to an almost daily display of electrical storms over the valley and into Mozambique. The ploughing began the moment the rain was sniffed. This weekend I helped a friend at the village clear her field of thorn-bushes and stunted trees with some dry grass and a box of matches, ready for the plough, only to be attacked and sent running by a swarm of (now homeless) African bees. I look around me at huts I know so well. Everything family I walk past has been hit by mosquitoes, female circumcision, HIV. Not a family unscathed.

In the UK the government plan to expand current grammar schools and build new ones. In each of my last 3 schools in the UK I’ve had fascinating conversations with parents battling with the choice of school for their child. I’ve listened to the inevitable, slightly awkward parental aside on an open morning tour; ‘Because she’s applied for grammar school X we’ll take the exam but I don’t think she’ll get it so we will probably see you in September’, with the corresponding message this gives to the child, and to the school.

Leaders and teachers working in grammar schools are all working hard with a selected ability group of students. The problem with grammar schools is their threefold impact on all other schools. Firstly the number of grammar places taken up puts pressure on local schools with already struggling budgets. Secondly there is no getting away from the academic impact for schools left behind having to adjust to life without the top 25% of the ability range. Future growth of grammars will only add more pressure on schools doing a good job and can only mean that achievement of local schools will drop. And thirdly there is the perceived impact – the neighbouring state school becomes an implicit second choice, however good it is, however well led. It’s tough being a Mum and a Dad in the UK’s education system, especially when political leaders create division and set educational leaders against each other.

For me the parable of Zimbabwean education is clear, and although it is a different context, made more extreme by the actions of a self-serving leader, the essential elements are similar to the UK: when you focus on and over-invest in a very small number of schools which educate the country’s decision-making elite, and when you believe that this is enough to become your strategy of ‘social mobility’, then the majority of that country’s schools will suffer. They cannot possibly compete equally to provide the best for all children and for all parents. You just cannot have it both ways.

The children of Zimbabwe still don’t have it easy either. When I consider the daily work rate of these children amongst the goats and the garden plots, their commitment to their broken schools and desperate desire to succeed in their studies is heroic. In a land where corruption is a much more likely quality in a government than dedication, and where there are so few role models, we must look to the system of education to be a beacon and create new and real futures for poor children. Along the dirt road, walking or running to school, in my mind’s eye I still see their faces light up with hope for the future. Their dream of what a great education can do for them is intoxicating. We need to learn the lessons from Zimbabwe.

Pingback: Why our heroes matter to children – ianfrostblog

The article is solid though biased.. I happened to be one of the pupils during Frost era.. We enjoyed ourselves at MARIST NYANGA.. THE SCHOOL REMAINS ONE OF THE BEST IN AFRICA.. Breeding directors of big telecoms companies like us

LikeLike

Hey Ian you taught me Geography at Marist Nyanga how are you keeping

LikeLike

.

LikeLike

Hello ian.enjoyed reading the article, largely correct

LikeLike