“I was much further out than you thought

And not waving but drowning.”

Stevie Smith

1.

Getting our teachers back:

The moment it hit home for me was when I heard that X had left teaching. I knew then with absolute clarity that we had a problem. Why in that moment? Because she was simply brilliant. Strong subject knowledge, super-high expectations, a great team player and a wonderful sense of fun. She was one of those incredibly effervescent adults who children of all ages gravitate towards. I had appointed her into a good department team where at first she thrived. In her first year she would sometimes have the kind of meltdowns we’ve all had – mostly around the volume of marking, unhelpful paperwork or working so late she had no energy for anything else.

But she was one of those professionals who I sensed, with a little creative support, would ride the storm and withstand the roller-coaster of the first two years. I’d visit her classroom at 5.30pm and tell her to go home. Her team would take her for a drink. I told her to stop marking for a few weeks so she could get the balance right. There was a cycle of marking, deadlines, personal frustration that she felt things were not getting better, and then a meltdown. She was upset that she couldn’t manage things better.

“A cocktail of box-ticking demands, ceaseless curriculum reform, disruptive reorganisations and an audit culture that requires teachers to document their every move.” Becky Allen, The Teacher Gap

I remember my first headteacher, the late Robert Buckley, who often took a young geography teacher to one side, catching him at exactly the right moments of exhaustion, reminding him that the first year was the hardest and that it would get better. It did, it became brilliant. But I needed those kind words. And good people around, who would frogmarch you to the pub on Friday after school for therapy: either to dispel any delusions of grandeur or pick you up after a week’s mauling by West London kids.

And then I heard that X had left the profession to become a youth worker. Which was great for the local youth. But desperately sad for the kids she was teaching, for her team and for the wider profession. Although it was only one person, for me it was like a flare signal going up that something was very wrong. I felt a sense of waste. The waste of talent and her training, and of the 25+ future years of brilliant teaching that our pupils and our schools have lost in that decision to leave teaching. It was not her fault at all. My strongest feeling was that we could have avoided this and caught her before she fell. I could have done more.

2.

Teachers leaving like never before:

There are currently 216,500 teachers in primary, 208,300 teachers in secondary, 16,700 teachers in special and a steadily growing 61,500 teachers in the independent sector. We are short of specialist teachers in maths and science (in poor areas outside London only 17% of physics teachers have a relevant degree compared with 52% in more affluent areas). Nearly 35,000 teachers left profession in 2015, and numbers are rising. Most leavers were in the 20-24 and 55-59 age categories.

“We know teacher recruitment targets have been consistently missed for many years. Workload, leading to a lack of leisure time and decreasing job satisfaction are key issues as well as a lack of flexible working particularly at a secondary level”. Stephen Tierney, Chair of Heads Round Table

Russell Hobby, Teach First Chief Executive feels that the government lacks the levers to address the teacher recruitment crisis and believes “devolution and autonomy” (the breaking up of education into self-governing trusts) means the hands of the DfE are tied. The accountability system is driving school behaviour to generate excessive workload, and the speed of transmission from Ofsted to recognise this and bring real change on the ground is “unbelievably slow”.

3.

So why is there hope?

But despite this I feel surprisingly positive about the future of teaching. Things are changing, just not from the top. There is broad understanding, a consensus, a movement among grassroots teachers and many school leaders that this has to change and that we have to be that change. No one else is going to do it for us. While in the last ten years the education system has prioritised structural reform and reorganisation (from LA-land to MAT-land) the profession knows it will now have to look after its teachers.

So like never before teachers are being proactive: Sharing strategies to shift behaviour in our schools so that first time teachers can now teach and not be crushed by disruption. Swapping knowledge-rich curricula and resources so that new teachers don’t have to start from scratch. Addressing workload, not with woolly ideas but through hard, well-designed structures (designing tighter working weeks, addressing wasted meeting time, streamlining marking and reporting), which allow teachers to get on with their job. There is some end-of-the-world-scenario-ing on edutwitter but there are far more shafts of sunlight. Our profession is beginning to look after its own.

![]()

4.

Love the ones you’re with:

What reasons are teachers giving for leaving?

- Teachers who left in their first two years because they were not supported effectively, not provided with personalised help and practical strategies.

- Many were sick and tired of the relentless drudgery of fixing behaviour in their own classrooms because it was not managed centrally, or where the marking workload sucked the fun out of classroom interaction.

- Those who, like Becky Allen herself, as she describes in ‘The Teacher Gap’, felt that was no deliberate programme to help teachers get better, and no sense that it actually mattered much if they improved as teachers or not.

- Young parents balancing the challenge of bringing up young children with teaching. And who might be much more likely to return part time if they believed that it was doable, with realistic expectations about planning.

- Many retired early because of some or all of the above. The grandmasters with 10 000+ hours of practised-skill, who may not know how much they and their timeless skills are valued.

Many teachers have left financially worse off having invested in teacher training fees (this week’s Teach First survey of Headteachers reported that writing off student loans was the most popular option for boosting recruitment). Teachers have moved to perceived less stressful jobs, or retired earlier than they might have. They make up some of the teacher gap and should be part of the solution. But for them returning will feel counter-intuitive. How can they be confident that the same pitfalls (isolation, workload, stress) will not happen again? How do we persuade them that the profession is on it?

For those near the end of their career: Other public services are ahead of the teaching profession. The ‘Retire and Return’ scheme shows the NHS being proactive about retaining good people with invaluable skills. Why re-hire a retired employee? For heads and employers, there’s a double win: retaining valuable skills and experience and potential cost savings by reducing recruitment costs, agency fees and employer pension contributions.

Teach First’s Russell Hobby may be critical of the system’s agility to produce more teachers, but at least he is doing something about it. The Time to Teach scheme is designed to attract newcomers to teaching, Reconnect to Teaching will support former teachers to return to the classroom, while a teaching assistant fast-track programme will aim to support schools in developing high-potential support staff. It’s a start, for schools in challenging context.

For those at the start of their career: I think retaining good new teachers is about deliberate in-school training programmes to develop teacher expertise:

5.

Teaching expertise:

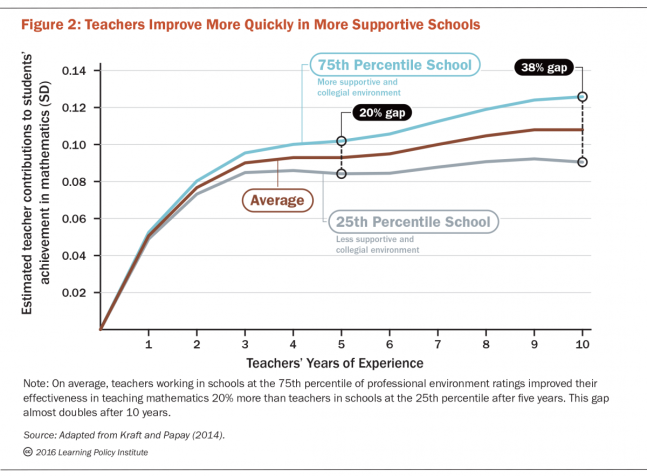

We hope that we get better at our job as we build experience. Becky Allen and Sam Sims borrow the graph below to describe the concept of a learning curve where over time our teaching skills and capabilities follow an upward trajectory. Just as measuring pupil learning is complex and not linear, the same is just as true for teachers’ progress. It is a difficult concept and tricky to measure but a helpful visual. While each person’s curve is unique, with a different start point and growth rate, what is common is a steep gradient after qualification and then more gently sloping until about the ten-year mark.

But teachers’ upward trajectories are not fixed. Schools that are really supportive of new staff (top blue line) find that teachers will gain nearly 40% more expertise compared with teachers in schools that do little. Common supportive practices include:

- teaching the same content in multiple years to build up expertise and decipher the misconceptions fast

- building up experience teaching a specific part of the course (and not teaching outside your subject)

- teachers working with skilled colleagues in curriculum teams to share planning and to benefit from the ‘spillover effect’ (including being given a subject mentor who meets without fail)

- Lots of planned opportunities observing skilled colleagues to learn the nuances of ‘professional judgment’ (eg. how do I develop a full repertoire of questioning skills, or when do I close down a class discussion).

Surely this is CPD. Maybe if X had received this kind of intentional support and training, which could have given her the tools to improve and develop mastery, she might be teaching now. Would she feel able to make her own decisions to keep her afloat and feel that sense of autonomy? Would the knowledge that she was improving her skills be the antidote to that sense of forever pouring out knowledge so much of the time but not being invested in? I really think it might have.

6.

Getting our teachers’ back:

Lucy Crehan believes the Finnish government’s support of teacher-mastery is right at the heart of Finland’s PISA success. Teachers qualify through a five-year Masters degree in education, funded by the government. Primary teachers study education for 5 years in one of the 8 universities that specialise in teacher training. For secondary teachers their education masters degree and their subject degree make up their 5 years of study and training. Crehan’s experience of working with Finnish teachers shows a deeply intrinsic motivation about serious study being a solid preparation for real autonomy as a professional teacher. The application process is tough and there is high demand for places. Both of these reasons are a big part of why the profession has so much more kudos and respect than currently in the UK:

“Since inspections were no longer needed Finnish teachers have had autonomy over how to teach and what resources to use, thus completing the triumvirate of relatedness, mastery and autonomy that supports intrinsic motivation.”

Lucy Creehan

This sounds like a country that really gets teaching. Invests heavily. Trusts teachers. Knows that schools are doing the right things. Trusts schools to deliver an education a proud country can be proud of. Now wouldn’t that be good? Getting our teachers’ back, if you see what I mean.

But we too have a responsibility too in how we talk up teaching. It’s a brilliant career where teachers have life-changing impact, and its one of the few professions with the potential to transform a community in a generation. We should be shouting from the rooftops, encouraging friends to consider it. If we are not evangelical about teaching, who will be?

Some questions our profession needs to consider:

- How will we build a profession where low stakes investment in teaching, not high stakes blame for terminal results, is central?

- How can we get back those who have left after less than 3 years and the ‘grandmasters’ who have retired too early?

- How do we make the first three years in a UK school a strong experience that does not break initial teachers nor deter newcomers to teaching?

- What can we learn about recruiting and retaining teachers from what America got wrong? (next post).

Excellent. Food for thought …

LikeLike

This situation demands for more attention!

LikeLike

Pingback: Small changes | ianfrostblog