photo by wildlifetrusts.org

photo by wildlifetrusts.org

A thing of beauty is a joy forever/Its loveliness increases; it will never/Pass into nothingness. Keats – from Endymion

Tipton: 1974. When I was young I had a love of natural history. Specifically newts. Near my house as a small boy I would idle away hours fishing in a wasteland pond with my dog on the edge of town (definitely something to be said for laissez-faire parenting in our overprotective culture). I would stand in silent solitude waiting for these semi-amphibian creatures to show themselves with their characteristic wriggle up to the surface to take in air.

I can remember like yesterday a Y5 project on newts that my teacher dreamt up and that I threw myself into. I grew to know and feel the colour differences between Smooth newt and a Palmate newt (sexy latin name Lissotriton helveticus: like a character from ‘Gladiator’). I drew colourful sketches of Great Crested newts, the Jurassic Park dinosaur of the trio, picking out the underside of their unbelievable bellies and their triceratops-like wavy ridge-crest, normally only properly visible in a jar. I wrote about them, drew them with precision, measured their growth and hatched their ‘efts’ (if there is a more poetic term for animal young I’d like to hear it). I sketched the incredibly rapid stages of their metamorphosis. I kept them, felt their feather-like gills and gazed at them with childlike awe for hours. It was muddy work, and I probably looked a like Huckleberry Finn, and stank of rancid pondweed. But what was not to like aged 10 and a bit?

Once I had an experience with newts which will remain with me forever:

We draw on our intense childhood experiences. Although traumatised for a while, I know that I loved my learning about amphibians in school and the extra research at home. My teacher sparked something exciting for a small boy and built on it, and at no point crushed my enthusiasm with a “that’s enough of that now”. Because of her planning and patience I knew with certainty that no one else in my class, nor any of my teachers, nor indeed any adult that I knew had spent as much time as I in the mini world of newts or had the depth of interest or fascination for them that I did. That sense of micro-awe and micro-wonder. Newts have become for me a metaphor of the ultimate hook (excuse the pun) into learning. A quality curriculum with really exciting content is at the heart of everything.

Our National Curricula (now twice round the block) too often force teachers to cover large chunks of content in a very superficial way. And because of our internet roller-coaster, attention-deficit culture, our children are used to racing through a shallow level of knowledge about lots of subjects and concepts. And we are under pressure to perform and get throughout the content. So how do we challenge and change the dominant culture around us? How do we embrace whatever we mean by ‘mastery’ and create schools which value digging deep into knowledge for its own good? How do we value depth not coverage? Where are our newts?

In Y5 the learning I was doing at school translated seamlessly beyond the school gates. ‘Project-based learning’ has been tried in secondary schools and found wanting, for lots of reasons. So where do we see children really get into flow in a meaningful way so they are utterly absorbed? This is Daisy Christodoulou’s frustration with our loss of the joy of facts and the fun of learning the ‘stuff’. This is where the teacher can step back, walk to the back of the class and admire. How do we create the space to slow things down so that our students practice so well that they feel that sense of awe, that pride in the final assignment, the finished article, the fourth draft of the poem, the completed model, the dance performance honed? The deep disposition within our children to be absorbed, curious, fascinated. Where memories are made.

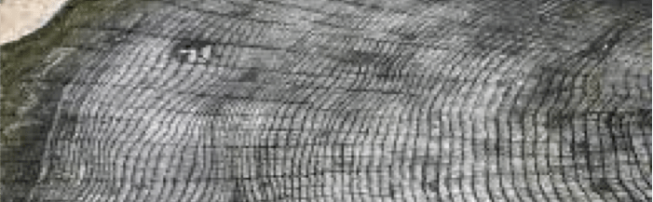

This differs from so much current ‘needs-must’ learning gleaning just the right amount of knowledge in order to reach a certain score in Y6 or grade 4 at GCSE. Aged 10 I might not have been able to master a sentence with a conjunction, but I could tell you why newts are semi-amphibian. I was inspired at school by being told how frogs reproduced, how the keys of a brass instrument worked, how and why patterns of burglaries varied in my town, or how to use the Cruyff turn to beat an opponent. My youngest son in his first term at university phoned me yesterday telling me how he had counted the heart rates of daphnia fleas on 3 different surfaces: water, caffeine and ibuprofen, to see the impact of these chemicals on them, and us. He will remember that. Stuff that is tricky. And fun. And also a little bit cool. The wonders of a great curriculum are like the annual growth rings in trees. Children should be learning it in 100 years’ time.

So 5 simple suggestions:

Don’t overcomplicate our classrooms and our learning: As a Head I a trying to encourage teachers to keep lesson planning very tight, teaching one or two really key concepts unbelievably well, often reteaching them and then allowing children to really drill this knowledge and understanding through different applications. Less is more. Let’s think carefully before we try to shove the next new idea into our lesson plans: see Phil Stock’s excellent Resist the urge – Joeybagstock

Scour our schemes of work: Our Heads of Faculty have spent lots of time this year drilling down into where the real content challenges are, and planning in more depth for these bits. And making homework harder, a little more ‘different’ and asking whether it is really practising the skills that children have been taught?Where are the ‘memorable moments’ or experiences from which other curriculum content can hang? Primary and Special Schools are often best at this: 50 things to do before…

Slow down: Let’s resist the compulsion to race onto the next topic. Let’s slow down our delivery and ask ourselves whether this is now time for students to redraft and rework. Jamie Thom’s ‘Slow Classrooms’ might just allow some of this reflection, and also leave teachers feeling less stressed out. Slow Teaching – Jamie Thom

Ask better questions : We are currently reviewing our Key Stage 3. All of it. Obvious questions are: do Y8 & Y9 have enough really challenging content? How much material is now being taught in Y8 which previously was being taught in GCSE years? Less obvious ones include: how good is our enrichment, and how does this add to the whole-child experience and get kids excited about school and about learning?

To get school improvement right get the curriculum right: To begin to impose a school culture of better teaching techniques or improved behaviour shifts without the fundamentals of rock solid curriculum experiences is short term, sticking-plaster, cart before horse school improvement.

A rich curriculum is a great cornerstone. The bedrock upon which we build everything else in our schools. It’s application may adapt slightly, but if we value its principles then its content should not shift much and ought to bring great depth, when cooked slowly. We don’t want to dumb down beautiful and difficult things, and the degree of difficulty is part of its beauty. It is why our children should be learning about the Human Genome Project, Quark theory and Keats. It is why they need to know calculus and be able to bring perspective to a charcoal drawing.